SUNDAY, JUNE 21, 2015 | WEST HAWAII TODAY

6C

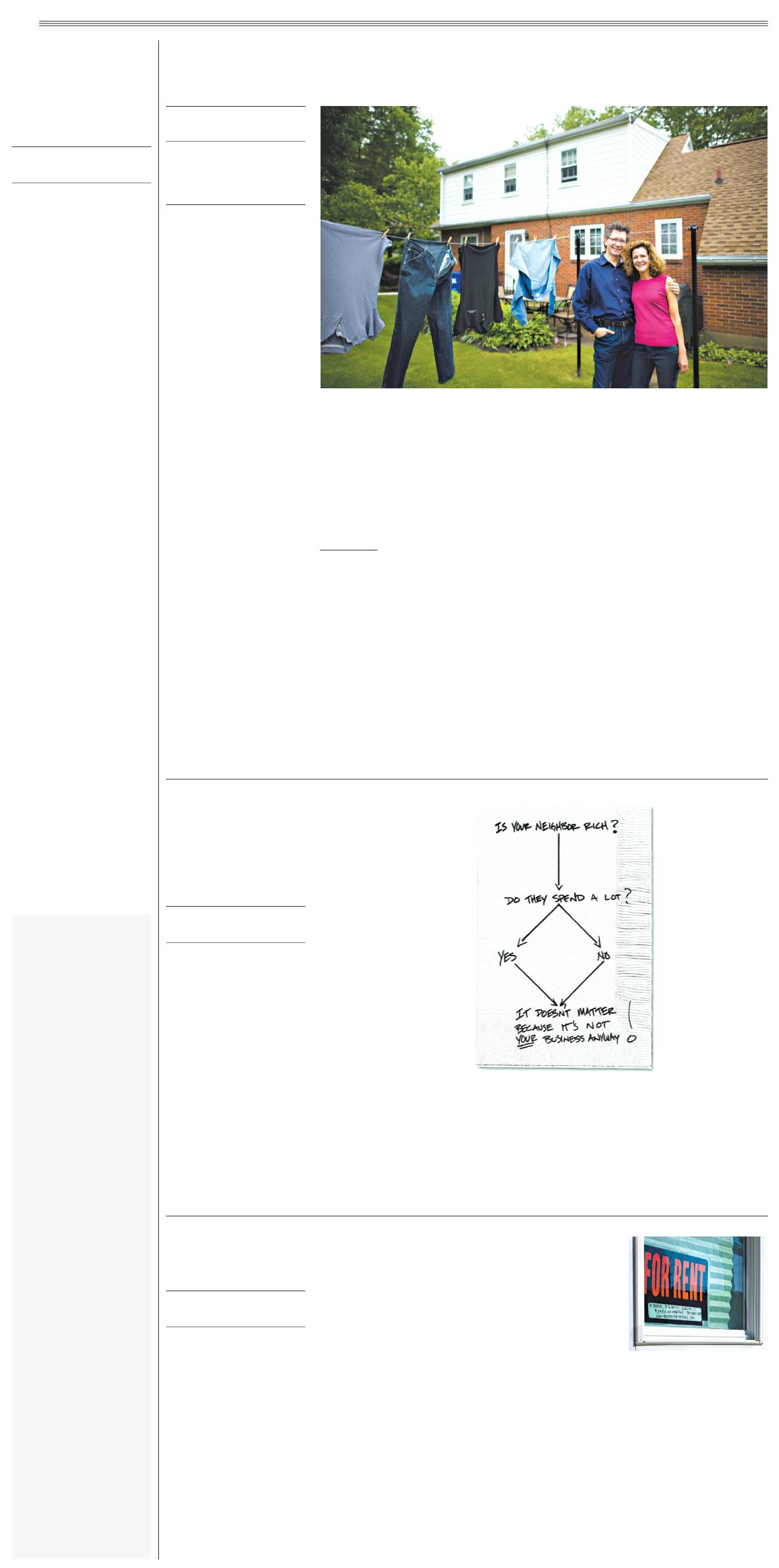

Bob Weidner likes to play a game

when he goes to a high-end outlet

store like Brooks Brothers: How

many things can he buy with

$100? On his last visit, the answer

was seven. “Every year, we go up

to the outlets and find a deal,” he

said. “It’s worth it.”

His wife, Angela Marchi, who

chides him for darning his socks,

prefers to buy her clothes twice a

year when her favorite stores put

last year’s styles on sale.

You wouldn’t know it from their

shopping habits, but Ms. Marchi,

56, a senior health care execu-

tive, and Mr. Weidner, 57, a senior

researcher at a large nonprof-

it company, are worth millions

of dollars. And while they own

three homes — condominiums in

Naples and Boca Raton, Fla., and

a house in Lebanon, Pa., where

they grew up, none are huge.

While the popular perception of

millionaires is that they are more

ostentatious than frugal, recent

research shows that single-digit

millionaires are far more mindful

about how they save, spend and

invest their money. “It’s about

paying attention to what makes

you happy and not just doing

what our society tells us to do,”

said Donna Skeels Cygan, a fi-

nancial adviser in Albuquerque

and the author of the book “The

Joy of Financial Security.”

“They look upon money as a

tool,” she said. “It’s an important

tool. They don’t neglect it, but

they also don’t worship it.”

A recent report from UBS

Wealth Management found that

people with more money are hap-

py. “I would say that millionaires

in general are very happy,” said

Paula Polito of UBS Wealth Man-

agement Americas.

What piqued my curiosity was

how conflicted the respondents

seemed to be about the source

of their wealth. They often have

jobs that entail long hours, high

pressure and working vacations.

“Part of this pressure to keep

going is less about greed and

more about insecurity that might

be self-imposed,” Ms. Polito said.

“If you ask people, ‘If you knew

you had five more years to live,

would you act differently?’ they

say they would. That’s a show-

stopper.”

I talked to people who had

what I considered an attainable

level of wealth. They had wealth

starting at several million dol-

lars. These were people who had

made the money as much by sav-

ing, investing and spending care-

fully as by making large salaries.

Steve Ingram, a lawyer in Al-

buquerque, said he and his wife

simply didn’t care that much

about material possessions. “We

have some nice things, but I drive

a car for 10 years and then trade

it in and get another car for 10

years,” he said. “We like to trav-

el, and we’ll spend the money for

that because it’s worth it having

a real experience together.”

Why the habits that helped

many of these people save mil-

lions of dollars persist when they

are wealthy is hard to say. They

may want to leave money to their

children. Or they may simply not

want for more than they have.

“Whether or not they realize it,

they pay attention to what makes

them happy,” Ms. Cygan said.

“They have selective ways to

spend on extravagances.”

Or they may not be comfort-

able spending because they have

worked and saved their whole

lives, said Sandra Bragar of As-

piriant.

Either way, this group learns

from its mistakes. Ms. Marchi

said she and her husband had not

been immune to the siren song of

a large, beautiful home. They lost

money on two such houses when

they had to move for work.

She never imagined having

three homes, she said. Naples is

their permanent residence; the

home in Lebanon is close to fami-

ly. They bought the condo in Boca

Raton, where she works, cheaply

and pay less than they would pay

in rent. And while she said she

expected to lose money on their

home in Lebanon when they were

ready to sell it, she did not consid-

er that a mistake. She liked being

able to stay close to her mother.

It’s an example of spending on

something that matters.

But are millionaires who darn

their socks just cheapskates? Or

are those habits part of the rea-

son they have achieved a level of

financial comfort?

“It’s interesting because it’s

less about greed,” Ms. Polito said.

“They’ve come from the middle

class, the working class, and they

still believe they’re part of the 99

percent, no matter what, because

that’s how they identify them-

selves.”

SKETCH GUY

CARL RICHARDS

A tendency to value

experiences more than

possessions.

YOUR MONEY

PAUL SULLIVAN

Staying mindful about

spending, even when

you don’t need to be.

Millionaires Who Are Frugal

Stop Keeping Up

With the Joneses

Rates Low,

U.S. Bonds

Lose Favor

‘White Lies’ Are Hurting Lenders

Government savings bonds ar-

en’t meant to be blockbuster in-

vestments; they are intended to

be safe havens for cash. But late-

ly, rates have been anemic.

New Series EE savings bonds

are earning 0.3 percent according,

to the latest update from the Bu-

reau of the Fiscal Service, which

sets rates for savings bonds on

May 1 and Nov. 1 each year. Series

I savings bonds — whose interest

rate combines a fixed rate set for

the life of the bond with a rate that

varies based on inflation — are

earning zero. “There’s not a lot

of motivation to buy them right

now,” said Mckayla Braden of the

Treasury Department.

Savings bonds also have be-

come less attractive to people who

liked giving paper versions as

gifts for birthdays or graduations.

Now, saving bonds are digital and

must be purchased through the

TreasuryDirect website, which

many users find cumbersome.

You can give electronic bonds

and print out a certificate to give

something tangible to the recipi-

ent, but, said Jane Bryant Quinn,

a personal finance expert, “It’s

not as appealing as it used to be.”

Still, the value of savings bonds

currently outstanding is about

$158 billion, according to the

Treasury Department. For older

Americans, in particular, “sav-

ings bonds are part of their cul-

ture,” Ms. Bryant Quinn said.

When deciding to cash in sav-

ings bonds, don’t simply cash in

the oldest bonds first, since they

may be paying higher interest

rates than newer ones, Ms. Bry-

ant Quinn said.

You can check a bond’s interest

rate and value on the Treasury-

Direct website, or on sites like

SavingsBonds.com.

Another reason to pay atten-

tion to timing when you cash in,

Ms. Bryant Quinn said, is to avoid

missing out on a scheduled inter-

est payment.

The interest earned on savings

bonds is subject to federal tax

when the bonds are redeemed,

but is exempt from state and lo-

cal taxes, according to the Inter-

nal Revenue Service.

In general, you must hold sav-

ings bonds for at least one year,

with some exceptions. If you hold

savings bonds for less than five

years, you’ll forfeit the most re-

cent three months of interest as

a penalty.

Q & A

¶

Does it make sense to buy

Series I bonds now, with

rates at zero?

Katie Bryan, a spokeswom-

an for the America Saves

program, acknowledged that

it’s difficult for consumers to

get enthused about savings

bonds when rates are so low.

But inflation may pick up.

Timothy Flacke, who runs

a nonprofit group that

promotes savings, said that

while I bonds bought today

won’t earn interest for the

next five months, at least,

it’s “highly likely” that over

the course of holding the

bond, it “will pay more than

zero percent.” He added,

“Even if you buy an I bond

at zero now, you still have

that inflation protection.”

¶

Do savings bonds ever

stop paying interest?

Both EE and I bonds stop

paying interest after 30

years. If your bonds have

matured, you should redeem

them. While most new sav-

ings bonds must be bought

electronically, you can still

redeem paper bonds at

many financial institutions.

John Gugle, a financial

planner in Charlotte, N.C.,

suggests checking with

your bank first. Mr. Gugle

said a client found that his

bank didn’t offer redemp-

tion services and had to

seek out an institution that

would redeem bonds he had

bought when his children

were small.

¶

Is there any way to buy

paper savings bonds?

Since 2010, taxpayers have

had the option of using part

or all of their federal income

tax refund to buy paper

I bonds. The minimum

purchase is $50, and the

maximum is $5,000. It is un-

certain, however, how long

the tax-time paper option

will continue.

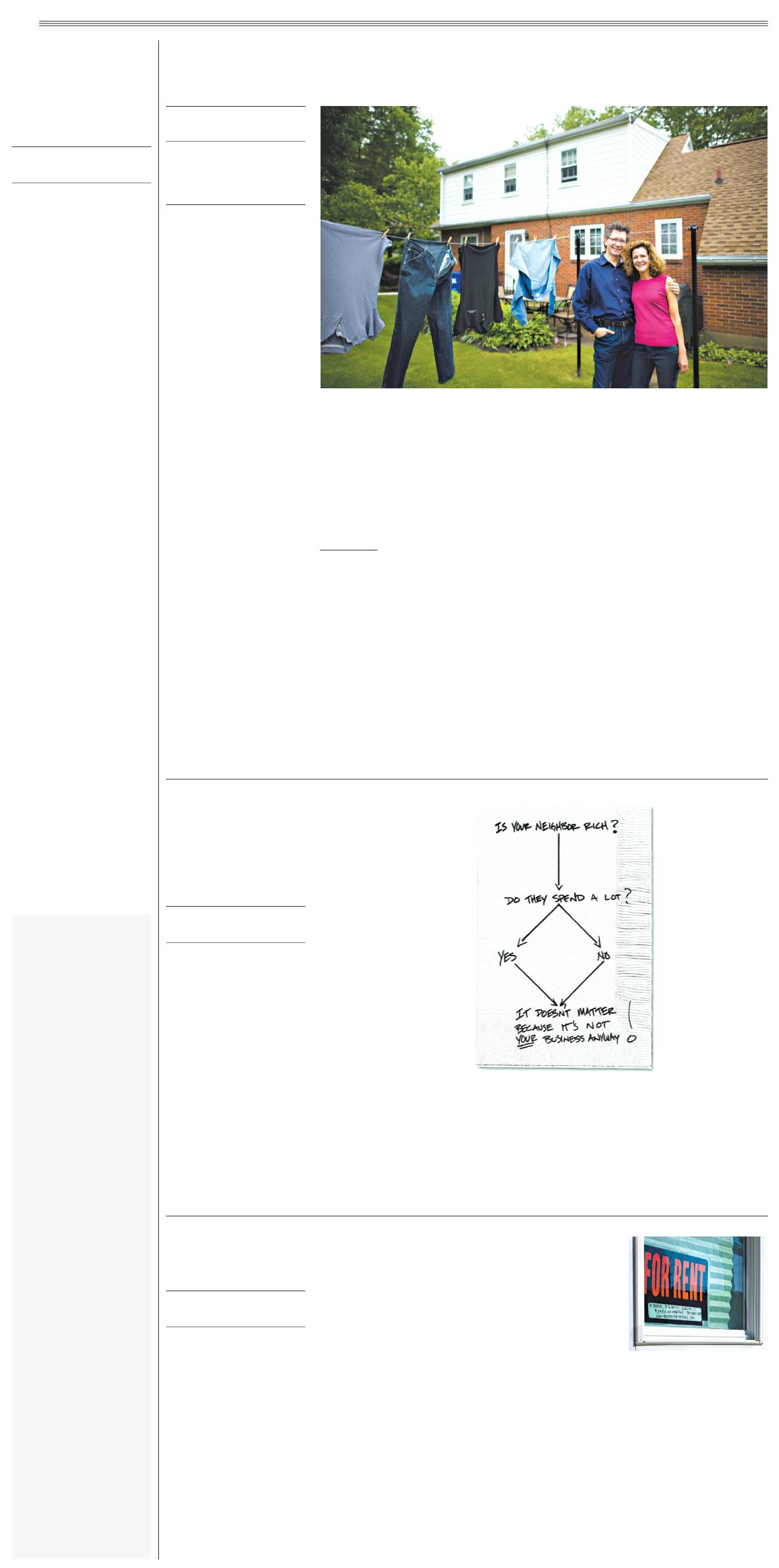

Humans can be a competitive lot.

The way we posture and position

ourselves to stand out in a group

seems to happen instinctively. Af-

ter all, in the past we competed

for resources and survival. Today,

we compete for different reasons.

Instead of food, we compete for

attention and social currency. To

figure out if we’re “winning,” we

use visual shortcuts, and money

offers one of the easiest ones. We

look around and compare how

we’re doing with what we see.

But there are a few problems

with this approach. We don’t

have access to our neighbors’

balance sheets, so we’re relying

on the consumption we see, not

true net worth.

Imagine you come home one

night and a neighbor pulls up in

a new Porsche Panamera Turbo.

(The sticker price starts around

$140,000.) You chat for a few min-

utes, and he tells you how much

he loves driving the car. Pause

for just a second. I want you to

make a mental note. What did

you think about your neighbor

and his car as you walked away?

I’m betting your thoughts

jumped to something like, “He

must make a lot of money,” or

“How can he afford that car?”

You made a judgment. You told

yourself a story based on what

you’d seen and what you’d heard.

See the problem? This story

relies on one fact. You know your

neighbor loves driving the new

car, but the rest of your story

qualifies as a fairy tale. Let’s add

a few wrinkles to this story:

¶ What if he took out a home

equity line of credit to cover 100

percent of the car’s price?

¶ What if he recently sold his

business for $1 billion and, as a

percentage of his net worth, the

new car is a drop in the bucket?

¶ What if he got a new job at

the Porsche dealership, and he

gets to drive the car as a demo?

Your story changes if any of

these facts proves true. Your

neighbor may be rich. He could

be leveraged to the hilt. You just

don’t know.

I’ve been thinking a

lot about this subject

recently after a friend

recommended Byron

Katie’s work. I love the

clarity she provides

with the idea that there

are only three kinds

of business in the uni-

verse: my business,

your business and

God’s business.

I know we like to

compete. But we’ll al-

ways lose if we’re judg-

ing ourselves based on

stories that rely solely

on someone’s demon-

strated consumer be-

havior. Luckily, we

don’t need an outside

force to solve the prob-

lem. We just need to

stop competing and

realize that our neigh-

bor’s business isn’t our

business anyway.

Meddling in our

neighbor’s business rarely leads

to good outcomes. That leaves

our own business. Plus, staying

focused on our business comes

with a side benefit. We no longer

need to worry about our ranking

or anyone else’s … because we

realize it’s none of our business.

Mortgage lenders have good rea-

son to require borrowers to spec-

ify whether they intend to live in

a house they are financing.

“If it’s not your primary res-

idence, the chance of you de-

faulting is very high versus your

primary residence, where you’re

living with your family,” said Tim

Coyle, the senior director for fi-

nancial services at LexisNexis

Risk Solutions, which develops

risk mitigation tools for banks.

On a loan application, borrow-

ers must attest to whether the

residence is a primary, second

or investment property. At clos-

ing, they must sign an affidavit

saying they will occupy the home

within 60 days of closing. But

some borrowers who plan to rent

out a property rather than live in

it aren’t truthful about their in-

tent — a form of misrepresenta-

tion called occupancy fraud.

“People will try to get an own-

er-occupied loan as opposed to

an investment property loan be-

cause you can get a higher loan-

to-value, meaning a lower down

payment, on a primary,” said

John T. Walsh, the president of

Total Mortgage Services in Mil-

ford, Conn. “And you’re going to

get a better interest rate on an

owner-occupied.”

Occupancy fraud represented

19 percent of all mortgage mis-

representation on loans delivered

to Fannie Mae in 2013, making up

the largest category of fraud af-

ter misrepresentation of debt li-

abilities. False occupancy claims

have since declined, according

to the 2014 fourth-quarter fraud

report released last month by

Interthinx, another provider of

risk mitigation tools. By its own

measure, occupancy fraud was

down 6 percent from a year ago,

a decline that correlated with

fewer loans involving borrowers

with multiple loan applications

on file, or using straw buyers.

(Straw buyers obtain mortgages

for those who would not qualify

for a loan.)

Occupancy fraud is costly to

lenders because it can raise the

default rate and the risk that,

if a fraudulent loan is exposed,

the loan investor (like Fannie

Mae) could require the lender

to buy back the loan. Lenders

are getting better at rooting out

false occupancy claims. Among

the red flags are borrowers with

mortgage applications pending

elsewhere, or an unusually long

commuting distance between the

borrower’s place of employment

and the property to be financed.

LexisNexis has a new verifi-

cation of occupancy product that

applies a score to a borrower’s

potential for occupancy fraud,

Mr. Coyle said. The tool is for use

on applications for refinance or

home equity lines.

Many people think lying about

occupancy is “the white lie of

mortgage fraud,” he said. “But

it’s extremely costly to the banks

and financial institutions.”

BORROWING

LISA PREVOST

INVESTING

ANN CARRNS

MARK MAKELA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

LESSONS LEARNED

Bob Weidner and Angela Marchi are worth millions, but choose not to live that way. The couple

has been burned by owning extravagant homes. They bought this house in Lebanon, Pa., to be close to family.

RICHARD PERRY/THE NEW YORK TIMES

OCCUPANCY FRAUD

Some

borrowers who plan to rent out a

property rather than live in it lie

about their intent in order to get

better mortgage terms. This can

raise the loan default rate.

WESLEY BEDROSIAN