GET MORE

FROM

West Hawaii Today!

As a West Hawaii Today subscriber, you have complimentary access to the e-edition.

Log on to hawaiitribune-herald.com and click on the e-edition button to get started today!

westhawaiitoday.com | 327-1652

BONUS! Get unlimited access to Star-Advertiser

and The Washington Post digital editions.

Log on to staradvertiser.com/whtactivate

Benefit available through an agreement withTheWashington Post and is subject to change or cancellation at any time

without prior notice.Benefit available to current print subscribers toWest HawaiiToday only and is non-transferable.Limit

one freeWashington Post Digital Premium subscription per person.Additional restrictions may apply.

5C

WEST HAWAII TODAY | SUNDAY, JUNE 21, 2015

MANAGING YOUR MONEY,

WORK AND SUCCESS

Copyright © 2015 The New York Times

SpendingWell

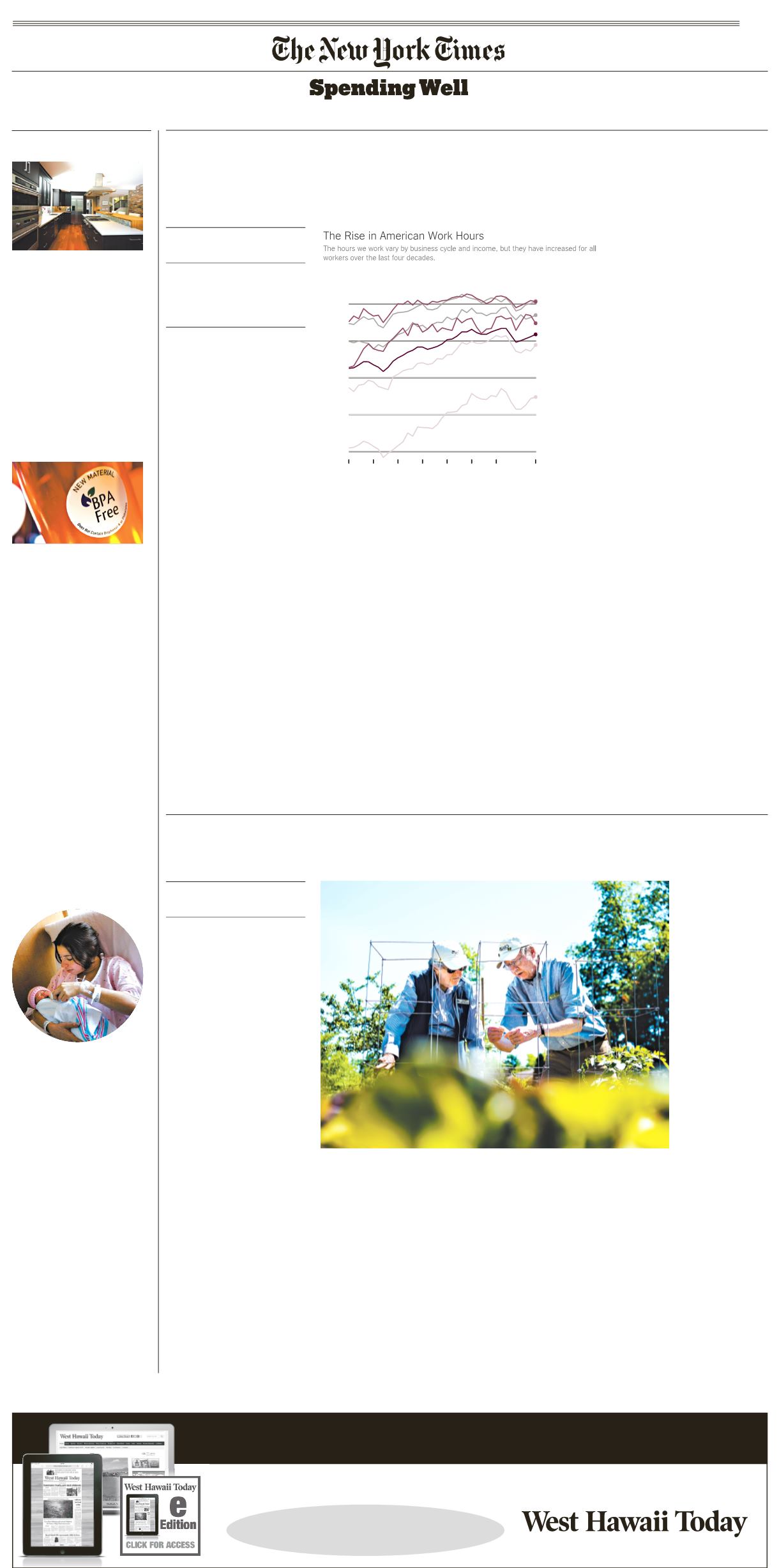

Average annual hours worked by paid workers age 18 to 64, by wage percentile

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement microdata

2,000

1,800

1,600

1,400

1,200

All Workers

1st to 20th wage

percentile

20th to 40th

40th to 60th

60th to 80th

80–95

Top 5%

’75 ’80 ’85 ’90 ’95 ’00 ’05

’13

JACOB HANNAH FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

THE NEW YORK TIMES

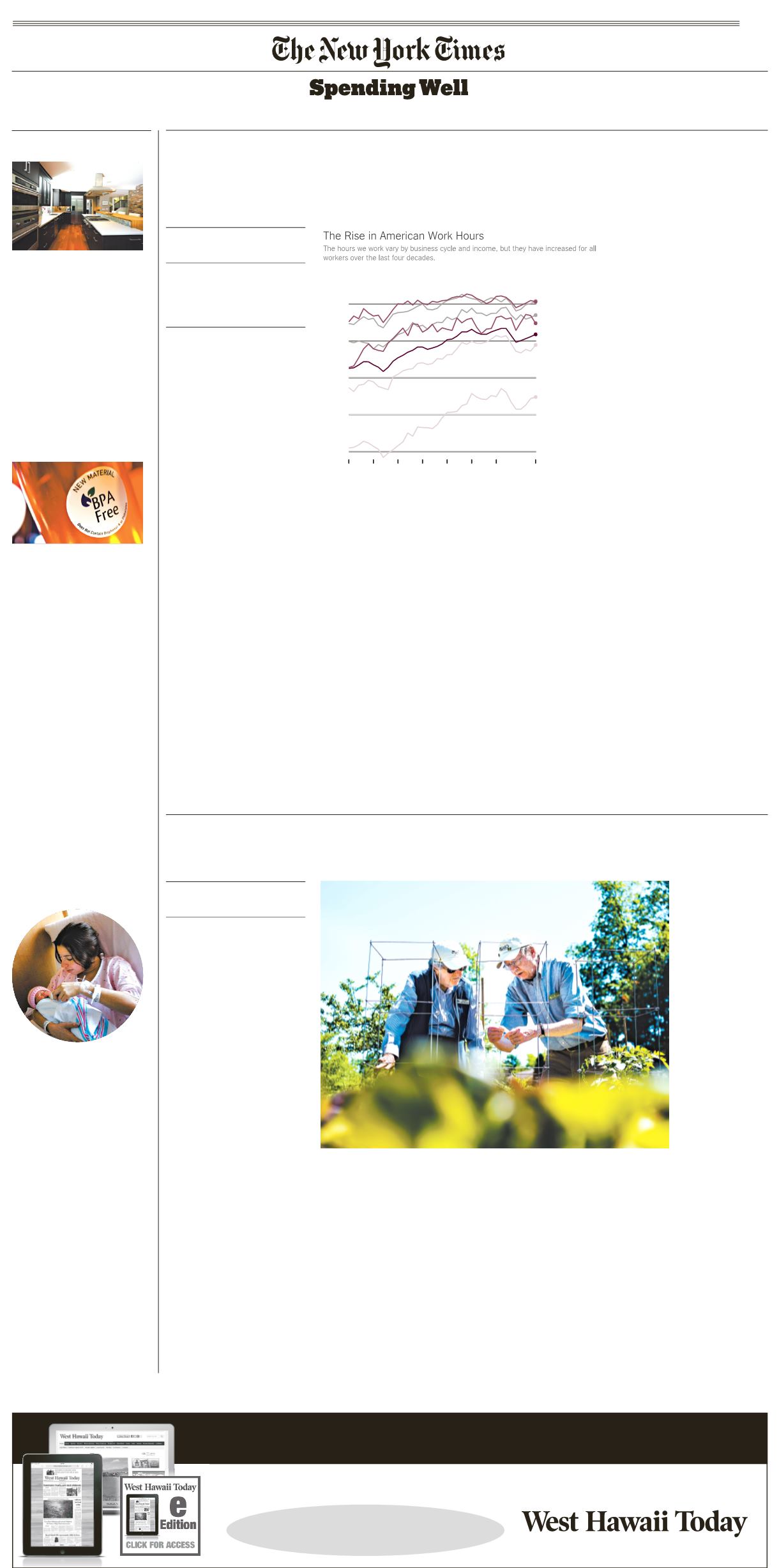

A die-hard community gardener

and composter, David Conrad,

77, wanted to age in a retirement

community that complemented

his love of all things green. So

seven years ago, he and his wife,

Sally, moved to earth-friendly

Wake Robin in Shelburne, Vt.

Now Mr. Conrad spends his

days managing the recycling

campaign, working in the com-

munity garden and walking the

community’s four miles of wood-

ed trails..

“I wanted to live in a place

that’s healthy,” said Mr. Conrad,

a retired college professor. “So

sustainability is very important.

We like to think that we’re lead-

ing the way.”

Green do-gooders like Mr. Con-

rad are forging a new path for

retirees. Though eco-conscious

retirement communities are

rare in the United States, they

are expected to grow in number

as baby boomers age and seek

healthier, greener alternatives.

These lush facilities offer lots

of unseen benefits. Carbon foot-

prints are reduced with energy-

and water-saving initiatives, in-

cluding geothermal heating and

low-flow toilets. And older peo-

ple can enjoy environmentally

friendly buildings that typically

offer airy spaces with more nat-

ural light and indoor furnishings

that use far less toxic materials.

The challenge is wading

through the policy of green stan-

dards. “Eco-friendly doesn’t

mean a lot,” Mr. Hopkins said.

“And some places just use buzz

words.”

Two types of official green stan-

dards can serve as guideposts.

The first, said Mr. Hopkins, is En-

ergy Star ratings on appliances,

a government label that desig-

nates energy efficiency. Second

is a community’s LEED certifica-

tion, a program put together by

the U.S. Green Building Council

to create healthier, more ener-

gy-efficient buildings. There are

four levels: certified, silver, gold

and platinum, the highest rating.

Getting this label requires lots

of adjustments, and energy effi-

ciency is only one of them. Oth-

ers include choosing drought-re-

sistant plants, using recycled

materials and installing large

windows for natural light.

Green retirement communities

are largely upscale and in the

Northeast and Northwest. Take

Atria Woodbriar Place, a gold

LEED-certified senior campus

in Falmouth, Mass. Appliances

are Energy Star rated and solar

panels generate some of the com-

munity’s electricity.

Roberta Hendricks, 81, says

she likes Atria Woodbriar be-

cause it has resource efficiency

that’s more difficult to create in

an existing home, such as low-

flow toilets and water-saving de-

vices. “What better life could you

have?” she asked.

“Energy is saved in

every way.”

Wake Robin pre-

dates LEED certi-

fication. But it has

added geothermal

wells and other

ene rgy - e f f i c i en t

upgrades over the

years. Some Wake

Robin

residents

with green agendas

also pitch in. Mary

Hoffman, 88, works

with the staff to find

ways to conserve

energy and encourage recycling.

In Portland, Ore., Rose Villa

has turned itself into a sustain-

able community. It has a garden,

the dining room gets organic pro-

duce from local farms and there

is a composting program. But the

community is not LEED-certified

because making the changes that

the certification requires can cost

tens of thousands of dollars, said

Vassar Byrd, chief of Rose Villa.

“There are so many ways to

focus on green,” she said. “You

have to decide what’s important

to you.”

For Mr. Conrad being green is

a necessity. “I want to leave the

world a little better,” he said.

RETIRING

CONSTANCE GUSTKE

Talking Points

Goldman Sachs Plans Loans

For the Average American

Goldman Sachs, which has

largely served as the bank of

the powerful and privileged for

146 years, is working on a new

business line: providing loans to

help you consolidate your credit

card debt or remodel your kitchen.

Goldman plans to offer loans of a

few thousand dollars to ordinary

Americans and compete with

local banks. The new unit hopes

to make its first loans next year

through a website or an app.

Cutting BPA From Cans

Some food giants like General

Mills and the Campbell Soup

Company have shifted from using

bisphenol A, or BPA, a chemical

used in the coatings of canned

goods to ward off botulism and

spoilage. But companies do not

disclose which products are now

BPA-free, so consumers do not

know which cans to buy. Studies

linking BPA to developmental

and reproductive health problems

go back decades.

Montana for Entrepreneurs

Silicon Valley gets the glory, but

the hotbed of American entrepre-

neurship appears to be Montana.

The state leads the nation in

business creation, according to a

new report. Researchers say the

oil boom has powered the three

states at the top of this year’s

ranking — Montana, Wyoming

and North Dakota— where a

drilling frenzy brought a rush of

development.

A Divide on Family Units

When it comes to family, the Unit-

ed States has a North-South di-

vide. Children growing up across

the northern part of the country

are more likely to grow up with

two parents than children across

the South. Evidence suggests that

children benefit from growing up

with two parents and states with

more two-parent families have

higher rates of upward mobility.

Seattle’s High-Tech Institute

Seattle’s academic and business

leaders have unveiled a plan to es-

tablish a new institute to strength-

en the region’s high-tech economy.

The Global Innovation Exchange

is a partnership between the

University of Washington and Chi-

na’s Tsinghua University. It will

open in fall 2016 with a master’s

program in technology innovation.

Microsoft will donate $40 million

to help the institute get started.

The biggest obstacle to women in

joining the highest ranks of the

business world is a lack of fami-

ly-friendly policies. That, at least,

has been the conventional wis-

dom, and it has been embraced

by progressive companies that

offer flexible schedules or allow

people to work from home.

But some researchers are now

arguing that the real problem

is the surge in hours worked by

both women and men. The pres-

sure of a round-the-clock work

culture — in which people are

expected to answer emails at

11 p.m. and take cellphone calls

on Sunday morning — is partic-

ularly acute in highly paid pro-

fessionals like law, finance, con-

sulting and accounting. Offering

benefits that help families is too

narrow a solution to the problem,

recent research argues.

“These 24/7 work cultures lock

gender inequality in place, be-

cause the work-family balance

problem is recognized as pri-

marily a woman’s problem,” said

Robin Ely of Harvard Business

School and a co-author of a study

on the topic. “The very well-in-

tentioned answer is to give wom-

en benefits, but it actually derails

women’s careers. The culture of

overwork affects everybody.”

The study examined an un-

named global consulting firm.

The firm asked the professors

what it could do to decrease the

number of women who quit and

increase the number who were

promoted. In exchange, the ac-

ademics could collect data. The

firm was typical in that employ-

ees averaged 60 to 65 hours of

work a week.

The researchers, who included

Erin Reid of Boston University,

concluded that the problem was

that “two orthodoxies remain un-

challenged: the necessity of long

work hours and the inescapabil-

ity of women’s stalled advance-

ment.”

The time Americans spend at

work has sharply increased over

the last four decades. We work

an average of 1,836 hours a year,

up 9 percent from 1,687 in 1979,

according to Current Population

Survey data analyzed by Law-

rence Mishel of the Economic

Policy Institute. High earners

work the most. Earners in the

60th to 95th percentile worked

about 2,015 hours in 2013, up

about 5 percent from 1979.

For elite workers, the challenge

is the conflict between family life

and a work culture in which long

hours have become a status sym-

bol. In the study of the consulting

firm, men were as likely as wom-

en to say the long hours inter-

fered with family lives, and they

quit at the same rate. One told

the researchers: “Last year was

hard with my 105 flights. I was

feeling pretty fried. I’ve missed

too much of my kids’ lives.”

Men and women dealt with

the pressure differently. Women

were more likely to take advan-

tage of formal flexible work pol-

icies, like working part-time, or

to move to less demanding posi-

tions.

Men either happily complied,

suffered in silence — or simply

worked the hours they want-

ed without asking permission.

About a third of them, according

to another paper about the same

firm by Ms. Reid, would leave to

attend their children’s activities

while staying in touch on their

phones. Decisions like these

tended to get men promoted.

When women tried the same

strategy, it usually didn’t work.

When a man left at 5 p.m., peo-

ple at the office assumed he

was meeting a client, Ms. Reid

said. When a woman left, they

assumed she was going home to

her children.

Underlying this disparity are

deep-seated cultural expecta-

tions about men and women.

Men are expected to be devot-

ed to their work, and women to

their family, as Mary Blair-Loy,

a sociologist at University of Cal-

ifornia, San Diego, has described

in her research. “It’s not really

about business; it’s about funda-

mental identity and masculinity,”

she said.

The researchers said that when

they told the consulting firm that

the problem was bigger than a

lack of flexible policies for wom-

en — that long hours were taking

a toll on both men and women —

the firm rejected that conclusion.

It is not surprising that compa-

nies prefer to focus on relatively

narrow fixes like more flexibility,

not more broadly on the culture

of overwork. They would have

little incentive to encourage their

employees to work less. Yet some

professions that also had round-

the-clock hours have figured out

alternatives. Certain doctors

have begun working in shifts, so

patients see whoever is available.

“Is it really necessary for peo-

ple to be on call 24/7? The answer

is increasingly no,” Ms. Ely said.

“These professions are beholden

to the whims of the client, and ev-

ery question has to be answered

immediately — but it probably

doesn’t.”

WORKING

CLAIRE CAIN MILLER

Women see careers stall

for taking advantage of

family-friendly policies.

24/7 Work Culture Exacts a Toll

DAVID M

c

NEW/GETTY IMAGES

LEAH MILLIS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

MATTHEW STAVER FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Green Retirement Communities in Demand

ECO-MINDED

SENIORS

More baby

boomers seek to

retire in sustainable

communities. David

Conrad assists Mary

Hoffman in her

garden at Wake Robin

in Shelburne, Vt. .