C

TROPICAL GARDENER

| IN THIS SECTION

HOME

SUNDAY, JUNE 21, 2015 | WEST HAWAII TODAY

BOOK EXPLORES INNOVATIONS OF

MODERN JAPANESE HOME DESIGN

MEETING A

CHALLENGE

C

hallenged to build homes that

create a feeling of light, space

and tranquility in some of the

world’s most densely populated areas,

Japanese architects have had no choice

but to think outside the box. Literally.

Basic elements like walls, windows

and floors are reinvented to solve

design conundrums, such as homes

built on footprints the size of studio

apartments or surrounded on all sides

by other buildings. Frequently, the

materials of choice are a combination of

reinforced concrete, wood and glass.

With interest in micro-housing

growing worldwide, such innovations

have made Japanese architecture a

leading force in contemporary home

design. A new book, “The Japanese

House Reinvented” (Monacelli Press)

by Philip Jodidio, surveys more than

50 contemporary homes, by both

emerging and established firms.

“Faced with the constraints of very dense

urban areas and a lifestyle that has long

taken into account small spaces, Japanese

architects and their clients have shown

a surprising willingness to experiment,”

writes Jodidio, who has written more

than 100 books on contemporary

architecture, including monographs on

architects Tadao Ando and Shigeru Ban.

The elegant houses in the book

seem almost miraculously livable

and show a way forward for

challenging architectural puzzles.

But they are not for the timid.

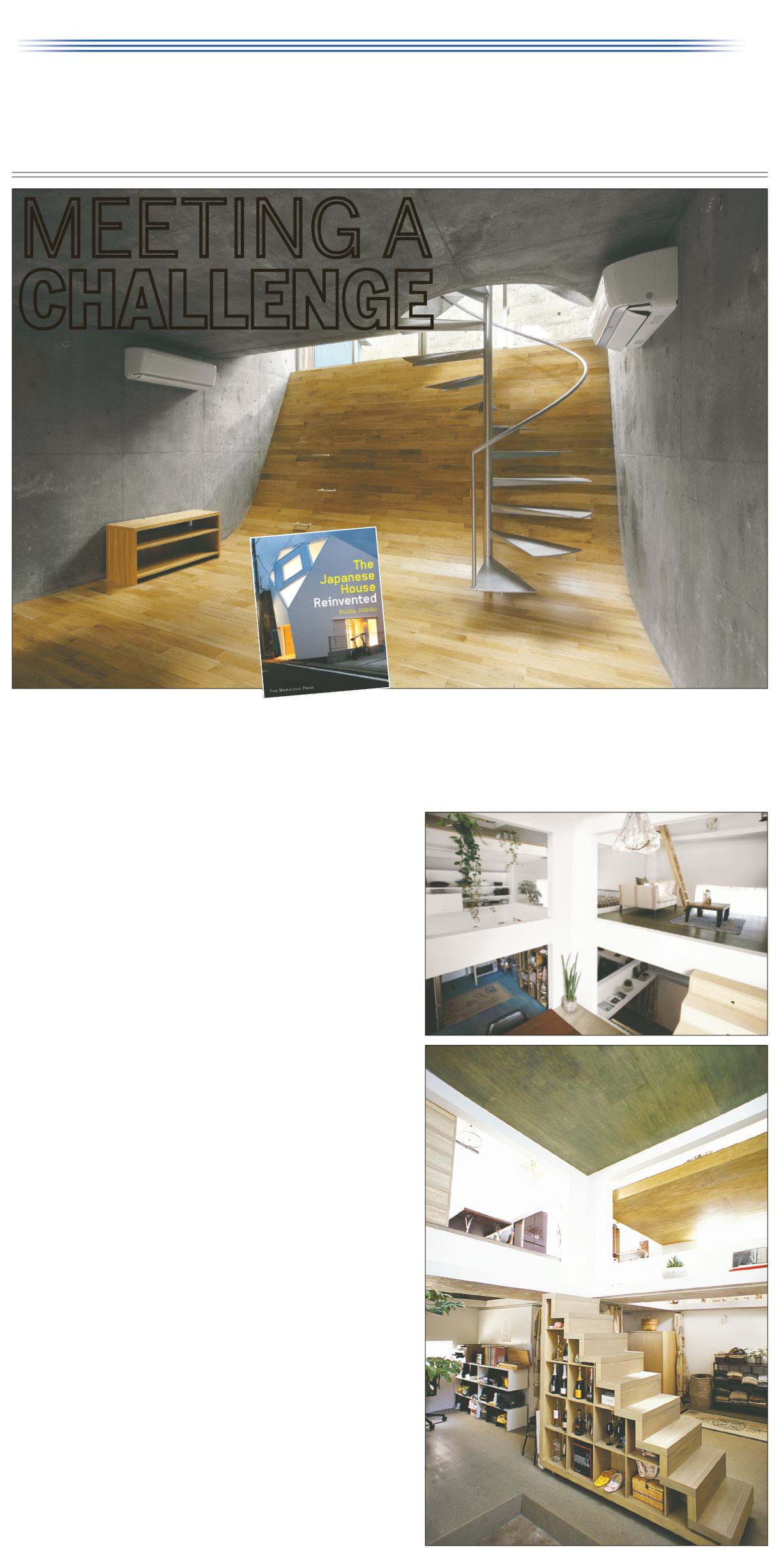

In a Yokohama house designed by

Takeshi Hosaka Architects, the basement

level of a 980-square-foot house features

a hardwood floor that slopes sharply

upward at one end toward the street-level

window above, resembling a sleek sort

of skateboard ramp. There is no defining

line between floor and wall. The ceiling, in

turn, slopes steeply upward, allowing for

an enormous, almost story-high window.

The unusual design creates an urban

basement with plenty of natural light and

privacy all at the same time, and gives the

diminutive two-story building the outward

appearance of being three stories tall.

An even tinier home in Tokyo, this one

designed by Koji Tsutsui and Associates,

features powerfully angled “bent boxes”

of reinforced concrete, which manage to

hide views of neighboring houses while

allowing in sunlight through a partially

sheltered balcony. There’s space on the

balcony for a few plants and small trees.

“For a house this small, surrounded on

all four sides, we had be really creative

about light, and the space had to be very

multi-purpose,” said Satoshi Ohkami,

an associate at the firm, adding that

many Japanese design solutions could

be applied elsewhere in the world.

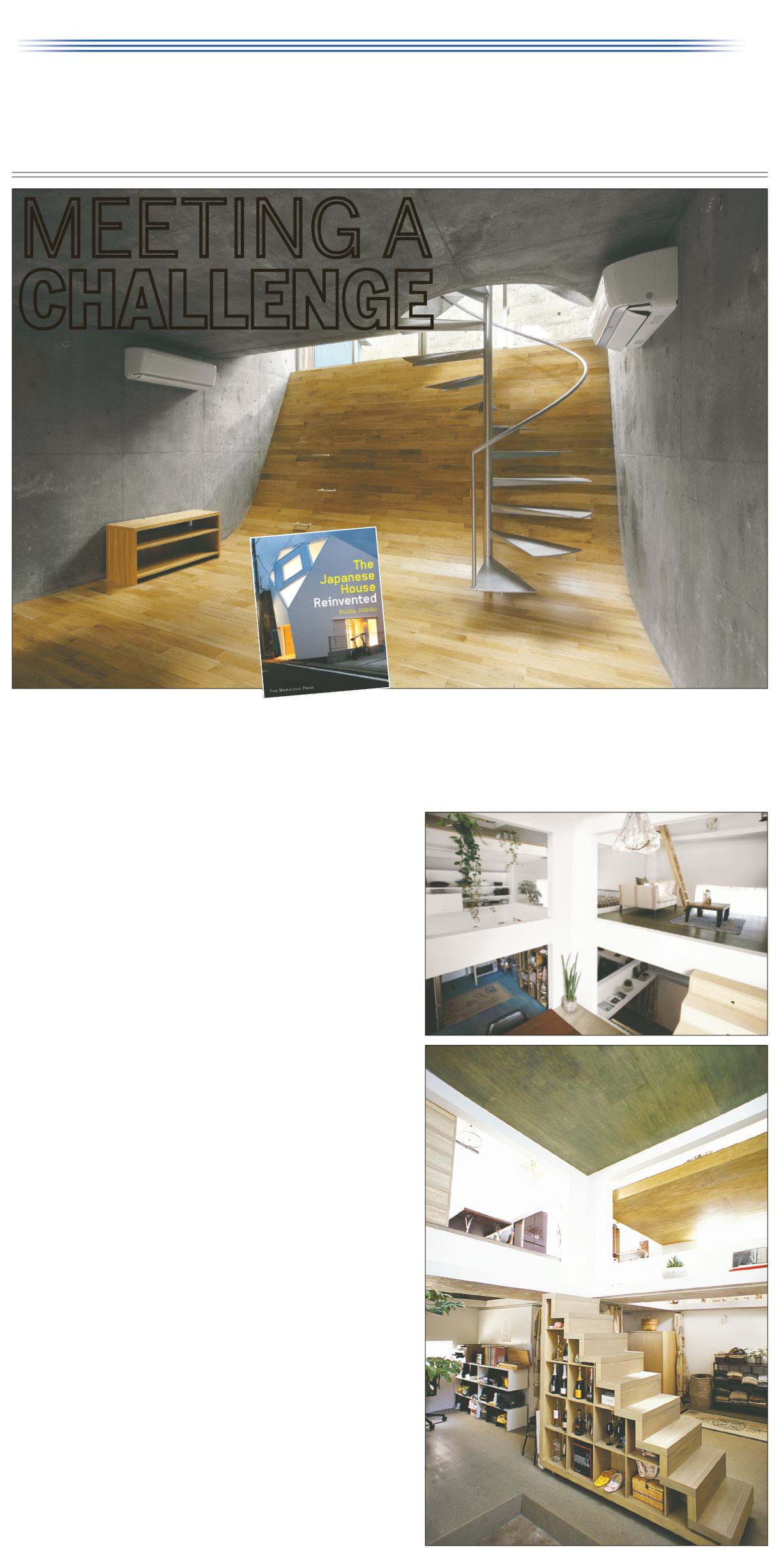

In a similarly small Tokyo house by

Hiroyuki Shinozaki Architects, a movable

staircase separated from the structure

allows for different shelf-like floor levels at

irregular heights, and rooms that can be

easily reconfigured for changing needs.

Not all the houses are

diminutive, however.

Like many Americans, Japanese tend

to prefer houses over apartments, and

roughly 60 percent of Japanese dwellings

are single-family homes, Jodidio writes.

Many of them are in dense urban areas.

See-through flooring, reflective ceilings,

plentiful balconies, mezzanines and

inner courtyards, and windows and

walls at surprising angles are more the

rule than the exception among homes

by these Japanese architects. Windows

come in all shapes and sizes, frequently

appearing at unexpected angles. And light-

drenched inner courtyards are juxtaposed

by frequently closed-looking exteriors,

some of which even conceal entries.

The architect Go Hasegawa designed

one Tokyo house with a louvered floor,

consisting of wood flooring with generous

slivers of open space between the

floorboards, giving the illusion of space

and allowing sunlight from a big upper

window to reach the ground floor.

“It is truly open. Air, sound, smell

and the everyday life of the family

come up and down through this

louvered floor,” Hasegawa said.

“Now is the moment we can innovate the

house and help create a new way of living.

Not only architects, but I feel clients,

also,” are engaged in that quest, he said.

Much as sliding, rice-paper

screens traditionally made indoor

areas more flexible in Japan,

intermediate floor levels and inner

open spaces add a feeling of space.

And the grandeur of nature is evident

in simple yet dramatic touches, such

as a single tree in a minuscule inner

courtyard or balcony, or a sliver of

visible sky at the top of a wall.

“We design minimalist and clean

design to get rid of clutter,” said Ohkami,

speaking from Mill Valley, California,

where his firm has a studio (Tsutsui

is currently a visiting professor at the

University of California in Berkeley). “We

focus on details and materials within

the space to create the character, and

the materials become very important.

Concrete is a lot more common in Japan

in the United States. People are hesitant

here to use concrete. I don’t know why

exactly. Architecture has to be flexible.”

BY KATHERINE ROTH

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The cover of the book, “The Japanese

House Reinvented,” by Philip Jodidio.

PHOTOS BY THE MONACELLI PRESS/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Above: “House T,” designed by Hiroyuki Shinozaki Architects/Tokyo.

“House in

Byoubugaura,”

designed by

Takeshi Hosaka

Architects/

Yokohama.

NACASA & PARTNERS INC